have you eaten? (re: "memories of murder")

the limits of translation, which is itself an art of loss.

koreans don’t tend to debone their fish — or i guess, to put it technically (?), we don’t eat filets. when it comes to fish, it doesn’t matter if we’re grilling it or braising it or frying it; we use the fish, bones and all. generally, that means that the process of eating korean-cooked fish requires more diligence and care, especially when it come to smaller fish and their smaller bones, which i know, some people just chew thoroughly and eat.

as a kid, i wouldn’t eat fish unless my mum would “발라” the fish for me, as in she would have to remove the meat from the bones because i was scared of the bones — they were sharp, and i was afraid they’d lodge in my throat, and i’d choke to death on them. she’d never scold me to “발라” my own fish, instead patiently removing little bits of meat and making a little pile on my plate, so i could scoop it all up easily with my chopsticks.

there is a variation of this scene you see all over korean film and television — someone reaching over to place food on someone’s bowl of rice. sometimes, it’s a chopstick-full of “발라”-ed fish. other times, it could be a piece of meat or kimchi or a choice bit of banchan, but the gesture is the same. sometimes, it’s accompanied by a piece of dialogue — “많이 먹어라" (“eat a lot”) — but dialogue is not necessary to convey what the scene is meant to say: you are loved, and here is where you are safe.

—

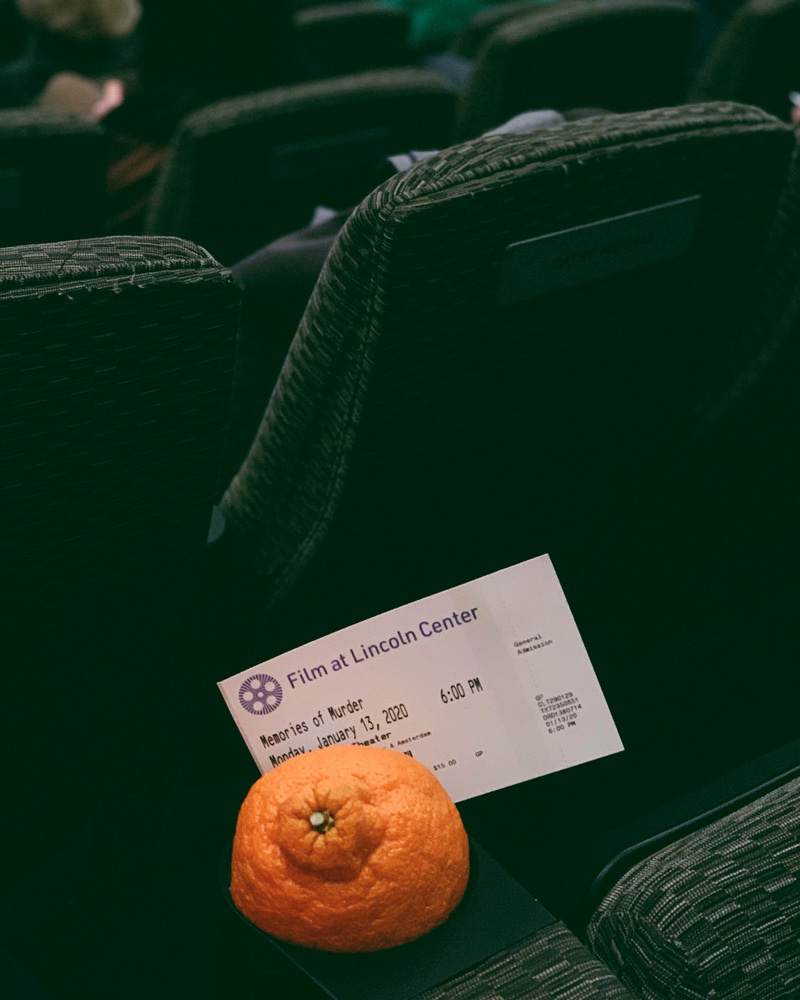

lincoln center is doing a retrospective of bong joon-ho’s films, so, on monday night, i went to see “살인의 추억” (memories of murder). the film was released in 2003*, and it’s based on the true story of the first (or, at least, most notorious) serial murders in korean history. between 1986 and 1991, ten women in hwaseong were found bound, gagged, raped, and strangled, usually by their own clothing. the rapist/murderer was never found — until 2019 when a man confessed to the serial rape/murders.

he was already serving a life sentence for raping and murdering his sister-in-law. he would not be prosecuted for the rape/murders.

the statute of limitations for the serial rape/murders had expired in 2006.

—

the climactic line in the climactic moment of the film was woefully mistranslated.

here’s the scene and context — and your “spoiler warning:” in memories of murder, song kang-ho plays detective park, one of the two lead detectives (the other, detective seo, is played by kim sang-kyung) on the serial rape/murder case. they’ve slowly been uncovering different details about the crimes — they always occur on rainy nights, and the same obscure song is always requested on the local radio station. the rapist/murderer has very soft hands, which means that he likely has an office job and doesn’t do manual labor. the victims are often wearing red.

the detectives are finally able to narrow down on one suspect, a young-ish dude with a desk job at the local factory. the crimes only started happening after he moved to their city. he lives alone, renting a room from a landlady. he has very soft hands. he seems like the likely culprit, but the only problem is that the detectives don’t have any solid evidence — until one of their forensic techs finds semen on the underwear of one of the victims. the only problem to that? this is 1980/90s korea, and korea does not have the technology to test DNA, so they have to ship their evidence to the US and wait for the results. they have no choice but to let their suspect go, though they keep him under 24-hour surveillance.

humans are flawed, though, and the suspect manages to slip away when seo falls asleep. in the morning, the body of a high school student is found, bound, gagged, raped.

mutilated.

murdered.

seo loses it. he’s not about to let this suspect live, fuck waiting for the DNA results, he’ll just get rid of this sorry ass himself. he drags the suspect out to the train tracks where he beats him before pulling out his gun. before he can pull the trigger, park comes running over, holding the DNA results in the air. seo feels triumphant — here is the long-awaited evidence that will put this scumbag away — only to read the results: inconclusive. the fancy labs in the US couldn’t prove the DNA from the semen sample matched the suspect’s DNA.

park can’t read english, but he can read seo’s body language as he slumps in defeat before retrieving his gun and aiming it at the suspect again. park manages to knock the gun out of his hand, but now he’s got doubts, too — was it this man? he’s really a boy, young and lonely. park has always been proud of his ability to read people but maybe he was wrong, he’s been wrong before, maybe he’s wrong this time, too.

as he holds the boy up by his collar and stares him in the eye, in the climactic moment, detective park mumbles, “밥은 먹고 다니냐?”

—

the subtitle reads, “do you just get up in the morning, too?” that may not be word for word because i scrawled this down after mulling over it during the movie, but it completely loses the reason that line — 밥은 먹고 다니냐? — is so impactful.

literally, the line means, “are you eating while moving about?” and there’s a strong sense of care lying underneath it, not necessarily of the suspect but in a more general way that betrays park’s exhaustion, which in turn stands in for the community’s exhaustion. this case has worn him thin and laid bare his weaknesses and incompetencies. it has injected fear into the community. the moment they’ve all been waiting for, hoping for, the answers they’d wanted to bring an end to this violence and terror, that moment has been lost.

in his moment of doubt, park isn’t questioning evidence or facts — he’s tapping into something much deeper, more human.

—

i dare say that, in korea, the question “밥 먹었니?” (lit. “have you eaten?”) is one of the deepest expressions of love there is. it’s the first question our 할머니s ask when we come home, what our mothers ask wearily even when they’re angry at us, how we show care and love and tenderness to each other. the symbol of a chosen family is that piece of meat, kimchi, or banchan placed on a bowl of rice; it’s expressed in one word, eat.

maybe you’re reading this and thinking, but, nana, food is how people demonstrate care in so many cultures, and here’s where i would say, yes! that is absolutely true, but also let me clarify: korea is a post-war country — or, actually, that’s not even fully accurate. korea is a country that is still in an active state of war. yes, recent generations are now more removed from actual war and its ravages, but my generation still grew up with the fingers of war touching us through our parents and grandparents. it’s also necessary to note that korea did not begin to prosper as a nation until the total butt end of the twentieth-century, so food still has a powerful emotional charge to it. we hear about koreans and their truly absurd emphasis on education and certain elite professions, but that stems initially from that post-war desire for parents to insure that their children would prosper, that they would never go hungry.

of course, that’s all become totally warped and etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. and, of course, food carries this added emotional weight in other countries and cultures as well.

memories of murder is set in south korea when it was a baby democracy, just emerged from military dictatorship. the decades before had seen so much violence and bloodshed, with the gwangju massacre in 1980 being the bloodiest, and student demonstrations were still ongoing. the government was still deploying the military, soldiers who were often just kids serving their mandatory two-year military service, kids still in their twenties, kids who were sometimes friends of those demonstrating students. in the movie, we see how curfews are enforced, how police officers aren’t even available to help in this search for this serial rapist/murderer because they’ve been sent over to the next city to suppress another demonstration, how korea is still a poor country where toilets are uncommon and forensic technology is behind.

this is the context in which detective park murmurs, are you at least eating while going about?

it’s important to note that he isn’t trying to humanize a possible rapist/murderer, and i don’t believe the line is meant to be interpreted necessarily as empathy for such a heinous human. however, park has been accusing the wrong suspects throughout the film, trying to force and coerce confessions, and, in this climactic moment of doubt, he has to pause. the DNA evidence, which was supposed to make their case rock solid, has apparently fallen through. maybe they were wrong. maybe he was wrong — again. park has often fallen back on declaring that he’s good at reading people, resting on that supposed strength of his even though he’s full of bluster and pretty inept as a detective. maybe he’s wrong about everything. maybe he really is unqualified to be a detective.

there are no careless lines in bong’s scripts; he doesn’t just throw dialogue away; and it’s a punch in the gut that this is what he utters in this moment of total doubt: 밥은 먹고 다니냐? it is just so basically, essentially human, one that can be turned around upon himself — are you eating, are you alone, has your loneliness made you a monster?

—

this is still a momofuku substack, but i haven’t been to a momofuku restaurant since december 29 when i ate at majordomo (omg their version of kalbi-jjim is SO good, though i could do without the raclette, which, it turns out, is too rich a cheese for me). i was supposed to go back to ko tomorrow night, but i had to cancel earlier this week because of my invoices being paid late, which makes me sad. maybe some greater being out there is trying to get me to be better about money — and to save me $300, which is fine because jua is finally opening this month, and their tasting menu, i believe, is $95. and i’m going to kochi, which is a $75 tasting menu. i guess i’m not actually being “better” about money, just distributing it more broadly to a wider variety of places?

i am very excited to eat from other korean american places in nyc, just like i’m super excited to eat the pizza at nishi, now that it’s available for lunch. i was never going to make it out to nishi to eat pizza at nine-thirty on sunday or monday evenings, so i’m glad they’ve put the pizzas on their lunch and brunch menus. hopefully, i’ll make it in this next week … at which point i will order two pizzas for myself. you know i spend a lot of my time looking at menus and deciding what to eat.

anyway, as far as translation goes, the thing is — i know that it’s impossible for any translation to convey all the weight this one line carries. you can’t give that kind of cultural context in a film, where there’s no space for footnotes or a paragraph of explanation, so i don’t fault the translator, even though i still have to squint (figuratively) and tilt my head to the side (again figuratively) to try to understand how “do you just get up in the morning, too?” came from “밥은 먹고 다니냐?” translation is a difficult, curious art.

—

*bong and main actor song kang-ho showed up after one of the screenings, and bong reminded the audience that, yes, he’s a fan of david fincher and zodiac … but memories of murder came out four years before zodiac, thanks very much. bong’s general amusement and borderline contempt of american audiences amuse me very much — and, yes, maybe “contempt” is too strong a word, but he truthfully (and rightfully) doesn’t think much of hollywood or american audiences.